*My website, RC Airplane World, is now for sale. Established 20+ years, big potential. Contact me through my contact page if you are interested!*

How helicopters fly and are controlled

Helicopters truly are amazing aircraft; how helicopters fly is what makes them such versatile machines, being perfectly suited to roles ranging from military use to fire fighting to search and rescue (SAR), and everything in between.

Helicopters have been around for centuries - well, the principle anyway - but it was Russian/Amercian aircraft pioneer Igor Sikorsky who designed, built and in 1939 flew the first fully controllable single rotor / tail rotor helicopter - the fundamental concept that would shape all future helicopters.

Helicopter versatility

A normal airplane can fly forwards, climb upwards, dive downwards and turn (and roll) to the left and right. A helicopter can do all this plus has the ability to fly backwards, move sideways in any direction, rotate 360 degrees on the spot and hover i.e. stay airborne with no directional movement at all.

Helicopters might be more limited in their speed than planes, but the incredible maneuverability mentioned above is what makes them so useful in so many different situations.

Above: the directions a helicopter can move in and the associated name of control.

Controlling a helicopter

Helicopters require a completely different method of control than airplanes and are much harder to master. Flying a helicopter requires constant concentration by the pilot and a near-continuous flow of minute control corrections.

A conventional helicopter has its main rotor above the fuselage, just aft of the cockpit area, consisting of 2 or more rotor blades extending out from a central rotor head (hub) assembly.

A conventional helicopter has its main rotor above the fuselage, just aft of the cockpit area, consisting of 2 or more rotor blades extending out from a central rotor head (hub) assembly.

A primary component is the swashplate located at the base of the rotor head. This swashplate consists of one non-revolving lower disc and one revolving upper disc. The swashplate is connected to the cockpit cyclic stick and collective lever and can be made to tilt in any direction, according to the cyclic stick movement made by the pilot, or moved up and down according to the collective lever movement.

But first, to explain how the main rotor blades are moved by the pilot to control the helicopter, we need to understand pitch angle...

Rotor blade pitch angle

Each rotor blade has an airfoil profile just like that of an airplane wing, and as the blades rotate through the air they generate lift in exactly the same way as an airplane wing does [read about that here].

The amount of lift generated is determined by the pitch angle (and speed) of each rotor blade as it moves through the air. Pitch angle is known as the Angle of Attack when the rotors are in motion, as shown below:

This pitch angle of the blades is controlled in two ways - collectively and cyclically.

Collective pitch control

The collective control is made by moving a lever that rises up from the cockpit floor to the left of the pilot's seat, which in turn raises or lowers the swashplate on the main rotor shaft, without tilting it.

This lever only moves up and down and corresponds directly to the desired movement of the helicopter; lifting the lever will result in the helicopter rising while lowering it will cause the helicopter to sink. At the end of the collective lever is the throttle control, explained further down the page.

As the swashplate rises or falls in response to the collective lever movement made by the pilot, so it changes the pitch of all rotor blades at the same time and to the same degree. Because all blades are changing pitch together, or 'collectively', the change in lift remains constant throughout every full rotation of the blades. Therefore, there is no tendency for the helicopter to change its existing direction other than straight up or down.

The illustrations below show the effect of raising the collective lever on the swashplate and rotor blades. The connecting rods run from the swashplate to the leading edge of the rotor blades; as the plate rises or falls, so all blades are tilted exactly the same way and amount.

Of course, real rotor head systems are far more complicated than this picture shows, but the basics are the same.

Cyclic pitch control

The cyclic control is made by moving the control stick that rises up from the cockpit floor between the pilot's legs, and can be moved in all directions other than up and down.

Like the collective control, these cyclic stick movements correspond to the directional movement of the helicopter; moving the cyclic stick forward makes the helicopter fly forwards while bringing the stick back slows the helicopter and even makes it fly backwards. Moving the stick to the left or right makes the helicopter roll in these directions.

The cyclic control works by tilting the swashplate and increasing the pitch angle of a rotor blade at a given point in the rotation, while decreasing the angle when the blade has moved through 180 degrees around the rotor disc.

As the pitch angle changes, so the lift generated by each blade changes and as a result the helicopter becomes 'unbalanced' and so tips towards whichever side is experiencing the lesser amount of lift.

The illustrations below show the effect of this cyclic control on the swashplate and rotor blades. As the swashplate is tilted, the opposing rods move in opposite directions. The position of the rods - and hence the pitch of the individual blades - is different at any given point of rotation, thus generating different amounts of lift around the rotor disc.

To understand cyclic control another way is to picture the aforementioned rotor disc, (the imaginary circle created by the spinning blade tips), and to think of a dinner plate sat flat on top of the cyclic stick. As the stick is leaned over in any direction, so the angle of the plate changes very slightly. This change of angle corresponds directly to what is happening to the rotor disc at the same time i.e. the side of the plate that is higher represents the side of the rotor disc generating more lift.

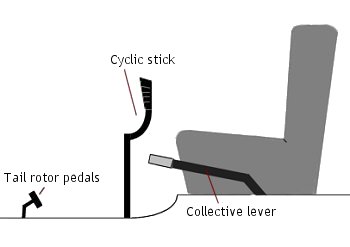

Above: the approximate layout of helicopter

controls in relation to the pilot's seat.

Rotational (yaw) control

At the very rear of the helicopter's tail boom is the tail rotor - a vertically mounted rotor consisting of two or more blades, similar to an airplane propeller. This tail rotor is used to control the yaw, or rotation, of the helicopter (i.e. which way the nose is pointing) and to explain this we first need to understand torque.

At the very rear of the helicopter's tail boom is the tail rotor - a vertically mounted rotor consisting of two or more blades, similar to an airplane propeller. This tail rotor is used to control the yaw, or rotation, of the helicopter (i.e. which way the nose is pointing) and to explain this we first need to understand torque.

Torque is a natural reactive force caused by any turning object. In a helicopter it is caused by the engine turning the main rotor blades; when the blades are spinning then the natural reaction to that is for the fuselage of the helicopter to start spinning in the opposite direction to the rotors. If this torque isn't controlled, the helicopter would just spin round wildly out of control.

So to beat the reaction of the torque, the tail rotor is used and is connected by gears and a shaft to the main rotor so that it turns whenever the main rotor is spinning.

As the tail rotor spins it generates thrust in exactly the same way as an airplane propeller does, the difference being that the helicopter tail rotor thrust is perpendicular to the fuselage. This sideways push of air prevents the helicopter fuselage from trying to spin against the main rotor, and the pitch angle of the tail rotor blades can be changed by the pilot to control the amount of thrust produced.

Increasing the pitch angle of the tail rotor blades will increase the sideways thrust, which in turn will push the helicopter round in the same direction as the main rotor blades. Decreasing the pitch angle decreases the amount of sideways thrust and so the natural torque takes over, letting the helicopter rotate in the opposite direction to the main rotors.

The pilot controls the pitch angle of the tail rotor blades by two pedals at his feet, in exactly the same way as rudder movement is controlled in an airplane.

NOTAR (NO TAil Rotor) is an alternative method of yaw control on some helicopters.

NOTAR (NO TAil Rotor) is an alternative method of yaw control on some helicopters.

Instead of a tail rotor to generate sideways thrust, low pressure air (created by a large fan in front of the tail boom) is expelled from narrow slots at the rear (side) of the boom. The slots are opened and closed by the pilot's pedals in the same way as tail rotor pitch is controlled.

The amount of air expelled effects the air pressure around the tail boom and the boom is 'pulled or pushed' one direction or the other, in response to the varying pressure and the natural torque being generated by the spinning main rotors. A natural effect (known as the Coanda Effect) involving air movement in relation to solid objects helps make the sideways movement of the tail boom happen.

NOTAR helicopters respond to yaw control in exactly the same way as tail rotor helicopters do and have a big safety advantage - tail rotors can be very hazardous while operating on or close to the ground, and in flight a failing tail rotor can easily result in a crash. In addition to that, NOTAR helis have a quieter operating noise level.

Throttle control

The throttle control is typically a 'twist-grip' on the end of the collective lever and is linked directly to the movement of the lever so that engine RPM is always correct at any given collective pitch setting. Because the cyclic and collective pitch control determines the movement of the helicopter, the engine RPM does not need to be adjusted like an airplane engine does. So during normal flying constant engine speed (RPM) is maintained and the pilot only needs to 'fine tune' the throttle settings when necessary.

There is, however, a direct correlation between engine power and yaw control in a helicopter - faster spinning main rotor blades generate more torque, so greater pitch is needed in the tail rotor blades to generate more thrust.

It's worth noting that each separate control of a helicopter is easy to understand and operate; the difficulty comes in using all controls together, where the co-ordination has to be perfect! Moving one control drastically effects the other controls and so they too have to be moved to compensate.

This continuous correction of all controls together is what makes flying a helicopter so intense. Indeed, as a helicopter pilot once said to me... "You don't fly a helicopter, you just stop it from crashing"!